In the early hours of Sunday 31 May, senior officers aboard the oil tanker Willowy were called to the bridge to be told that their ship and four others in its vicinity were mysteriously sailing in circles, unable to steer, and on course to converge.

It must be easy to panic at sea. The immediate presumption was that strong currents were pushing the vessels around, but there were no such currents where the ships were sailing in the south Atlantic Ocean, west of the South African city of Cape Town.

Ships appearing to sail in circles have become an increasingly common and mysterious phenomenon near a number of ports on the coast of China, especially near oil terminals and government facilities – but nothing had been seen where the Willowy was.

Researchers monitoring these bizarre circles near the Chinese coast believe they are probably the result of systematic GPS manipulation designed to undermine a tracking system which all commercial ships are required to use under international law.

Known as AIS (automated identification system), the technology broadcasts unique identifiers from each vessel – along with the vessel’s GPS location, course and speed – to other ships nearby.

These signals are even collected by satellites and used to monitor suspicious behaviour, including smuggling, illegal fishing, and – most relevantly – trade in sanctioned oil.

The circles spotted near the Chinese coast have been attributed to GPS interference, something which coincided with US sanctions on Iran, according to Phil Diacon, the chief executive of marine intelligence firm Dryad Global.

But according to a global analysis of this data by environmental groups SkyTruth and Global Fishing Watch, a number of circling incidents have also occurred quite a distance away from Chinese ports, with some impossibly appearing miles inland near San Francisco.

SkyTruth found the real locations of these ships often thousands of miles away from the circular sailing tracks. The ships were again were often actually near oil terminals or in locations where GPS disruption had been reported before.

At approximately 1am on Sunday morning, the Liberian-flagged crude oil tanker, operated by Singaporean business Executive Ship, suddenly swung starboard and began actually sailing in circles.

The ship was unable to steer and the crew reported that four other vessels in its vicinity were caught in a similar spiral, slowly converging on each other for an unknown reason.

“GPS interference can have serious consequences, with half of all casualties at sea linked to navigational mistakes,” as Mr Diacon told Sky News, although such interference targeting other vessels rather than the AIS tracking system is highly uncommon.

There are suggestions that GPS jamming has been used by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps to dupe commercial vessels into entering Iranian waters, and Chinese electronic warfare capabilities have been proposed as a potential cause for some ships appearing thousands of miles away from where they really were.

The crew aboard the Willowy were aware of these issues but none of these risks could be feasible west of Cape Town – a long way from the Strait of Hormuz or the contested South China Sea.

But the European Space Agency has detected something else there.

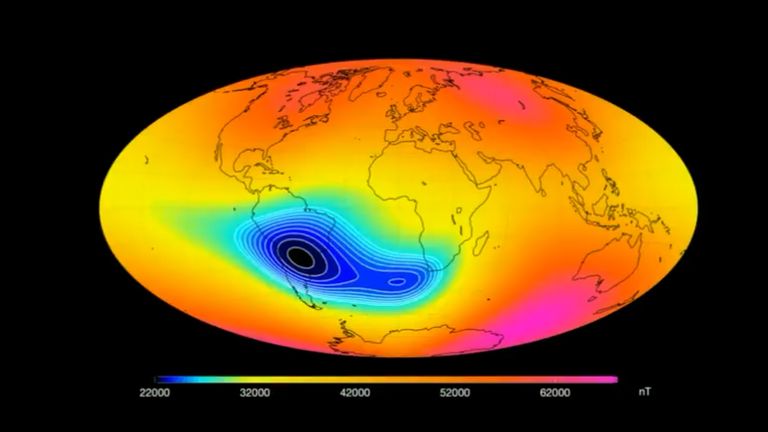

Nobody knows why, but the Earth’s magnetic field – which has lost almost 10% of its strength over the last two centuries – is growing particularly weak in a large region stretching from Africa to South America, impacting satellites and spacecraft.

Known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, the field strength in this area has rapidly shrunk over the past 50 years just as the area itself has grown and moved westward. And over the past five years a second centre of minimum intensity has developed southwest of Africa, very near to where the Willowy was sailing.

One speculation regarding this weakening is that it is a sign that the Earth is heading for a pole reversal – in which the north and south magnetic poles flip.

This flip won’t happen immediately but instead would occur over the course of a couple of centuries during which there would be multiple north and south magnetic poles all around the globe.

The impact would be enormous for seafaring vessels whose navigation was based on magnetic compasses – causing them not only to sail in circles, but perhaps not even realise it.

Fortunately, as the crew and the company’s onshore marine superintendents knew, it has been decades since magnetic compasses governed maritime navigation.

Modern ships like the Willowy use something called a gyrocompass instead, which finds true north as determined by gravity and the axis of the Earth’s rotation rather than magnetic north.

The gyrocompass is used alongside the ship’s other systems to detect true north, identify the vessel’s course, and steer it. If it was to fail it could cause exactly the issues which the Willowy was experiencing.

The crew, alongside the company’s shore-based marine superintendents, investigated and identified that the ship’s primary gyrocompass was indeed malfunctioning.

The ship resumed its course safely when it switched to using the secondary gyrocompass, along with an old-fashioned magnetic compass for good measure, Executive Ship confirmed to Sky News.

Asked what caused the failure, the company described it as “an incidental breakdown” and added “repair will be done at the next port where the cause will be identified by shore technicians”.

But what about the other ships in the Willowy’s vicinity, circling and seeming as if they would converge?

A spokesperson for Executive Ship explained to Sky News: “The initial presumptive cause of circling for the Willowy was considered to be strong currents which also led the crew to perceive that other ships were circling too.”

With so many mysteries on the oceans, it must be easy to panic at sea.

Source: The skynews

434580 916528Flexibility means your space ought to get incremented with the improve in number of weblog users. 232577